Hello hello,

I continue to be obsessed with the criminalization of poverty, and my obsession has slowly morphed into a general, deeper dive of class in America.

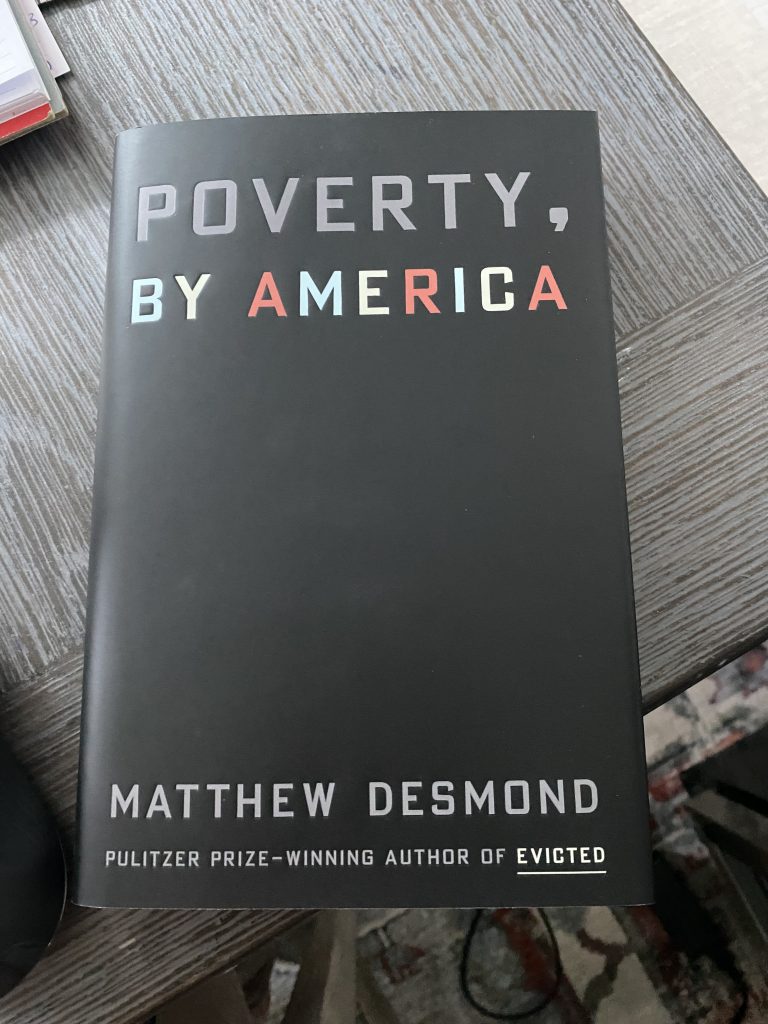

A recent book release is fueling this obsession. I am already a fan of Matthew Desmond’s work so I’ve been awaiting the release of his newest book called Poverty, by America. It just arrived at my doorstep so I haven’t read it yet, but Matthew was recently on the Some Of My Best Friends Are podcast – check out the episode here:

https://www.pushkin.fm/podcasts/some-of-my-best-friends-are/americas-poverty-is-by-design

While the whole conversation is thought-provoking and enlightening, I paused when I heard him outline the fact that we, as a society, have a general distain for poor people. We think people are poor because of some individual character flaw (e.g. they’re lazy or they aren’t trying… ahem cue gaslighting theme music). For anyone who isn’t ‘poor’, we fail to acknowledge all the advantages we’ve experienced; instead, we’re quick to think we’ve achieved our socioeconomic status in life based on our own merit (insert eye-roll emoji). There is so much to talk about on this topic that I’ll stop myself before I really get started! [Ok just one more thing, I can’t help but bring up the psychology of feeling poor vs. objectively being poor… and how comparison is the thief of joy:

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/01/15/the-psychology-of-inequality ]

It just so happened that this podcast episode with Matthew came out around the time of the implosion of the Titanic-bound subversive. There was public outcry about the inequity of the resource expenditure (and media coverage) to search for the 5 people who chose to go on that elective adventure compared to the concurrent sinking of a migrant boat off the coast of Greece with 200 onboard. [Another aside here – while writing this, I knew I didn’t need to spell out the fact that migrant = poor which is gross in and of itself. But that shouldn’t be the go-to stereotype because it shows just how narrowly we define ‘poor’. I have no doubt that there were lawyers and doctors and engineers on that ship, but we don’t always value intellectual capital when thinking about migrants. On the whole, we (the Western world) make base assumptions that are short-sighted and bias.] Based on memes about the ultra wealthy who could afford to take a ride down to see the Titanic, it’s fair to say the super rich in this situation are not well-liked either. So, it seems we don’t like poor people or rich people! [“We” means the ‘moral’ middle class…]

I’m just coming to terms with the fact that the real insight here is that the shame about either station in life (poor or rich) comes from within! We don’t need to wait for strangers to add external commentary to trigger our feelings about our lives – if you’re swimming in the water that is this American culture, you are probably fielding feelings about either extreme. And not just against the ‘other side’ as in poor people judging rich people or vice versa. If you rise out of or fall from your original socioeconomic station in life, that will trigger BIG feelings of shame. (So will raising children in a different socioeconomic status than the one you were raised in!) In conclusion – we judge others, but we also we vehemently judge ourselves.

On this theme, I’ve started listening to another new podcast about class in America called Classy with Jonathan Menjivar. Jonathan comes from a working class background but now lives on the “East Coast” [He says that in a way that assumes a collective understanding about what that means… hello coastal elites!], and he does things like buy cashmere socks. He hates that he wears cashmere socks because that’s not what ‘working class’ people do. Talk about the call coming from inside the house…

In the intro to the Classy podcast – there was an excerpt that really resonated with me. The host was interviewing a lady that was talking about actions she takes before the housekeeper arrives. She hides the $6 price tag on her loaves of bread because she *knows/feels* how ridiculous it is to pay that much for bread, and she doesn’t want the housekeeper to know. Jonathan (the host) asks, “You don’t think that the housekeeper already knows that you’re well-off?” [insert awkward pause] I feel that deeply. How do I downplay my privilege while still engaging in activities that only well-off folks can afford? I assume everyone feels this way, but maybe not. (???) Per usual, I have no answers, just many, many more questions. In the words of Jonathan Menjivar, “We’re looking at the people around us and either wanting more or feeling bad about what we already have.”

Check out the Classy podcast here:

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/classy-with-jonathan-menjivar/id1692818989

#powertoprivilege #courageousconversations #blacklivesmatter

Talk soon,

Jessica

PS – I’m not ruling out that we might all be in a simulation…. while all of these thoughts are swirling, I’m also bombarded with these themes in On Our Best Behavior: The Seven Deadly Sins and the Price Women Pay to be Good by Elise Loehnen. Particularly chapter 6 about Greed. Just by chance, I’m reading how Elise sums up the exact sentiment I’m trying to convey above; however, she adds a really interesting and poignant lens of gender and everything is amplified. Check it out!